This is news to me. I think any horror fan alive today should be grateful for the breadth and depth of the horror genre. Thanks to online resources and a more global market, we live in an age heretofore unmatched in the genre's history. If anything, I'm bummed by the idea of a top ten, because I could easily do a top twenty or top fifty. The last decade was just that good.

There are far too many honorable mentions to list here, so I may supplement this later with another ten movies...but in the meantime, put on some Europe and enjoy the countdown:

10. Frailty

Bill Paxton, 2001

Bill Paxton, 2001

One of the key questions in religion is how an all-loving God can allow suffering. The easiest solution? God is not all-loving. Frailty follows that idea to its logical conclusion, as a father (Bill Paxton) recruits his sons to help him kill demons who look just like normal people. Fenton (Matt O'Leary) doesn't trust his father's new purpose, but Adam (Jeremy Sumpter) wants to believe. Dad's certitude frightens, and the sequences with him kidnapping and threatening the seemingly innocent carry terrific gravity. This is a horror film where the horror matters. The performances by O'Leary and Sumpter are crucial to the film's success, and they feel perfectly normal and natural. It's ultimately their skills that make the film such an impressive chiller; even when they're off-camera, their lost innocence haunts us and reminds us that, if God exists, he's got some explaining to do.

09. The Host

Bong Joon-Ho, 2007

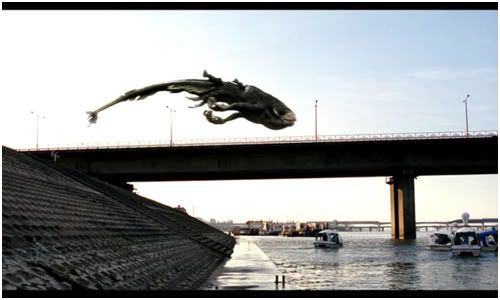

The Host is a horror movie. Has to be. Its creature is a nasty bit of ocean-spawn that chases down passers-by, gobbles them up alive, and plops them into a creepy underground lair. The film's heroes provide too little of a threat to this beast, which is a marvel of design and effects integration. Wait. Scratch that. The Host is a family melodrama. Has to be. Its heroes consist of a kindly grandfather, a slacker father, his plucky daughter, and her uncle and aunt. As they frustrate each other and strike out on their own, the movie shows that they work better as a team. Sure, not a lot better, but, hey. It's a big monster. Hold on. Nevermind. The Host is a satire. Has to be. This thing is as obvious in its indictment of modern threats as Godzilla was to the Japanese. Here, Americans create the monster by dumping toxins into South Korean rivers, and the Host is named so for the deadly virus it harbors. Imperialist satire? Pandemic sub-plots? There's too much here. Here's what matters: The Host rocks.

08. May

Lucky McKee, 2002

Lucky McKee, 2002

07. Rec

Balaguero y Plaza, 2007

Balaguero y Plaza, 2007

06. Session 9

Brad Anderson, 2001

Brad Anderson, 2001

05. Let the Right One In

Alfred Tomason, 2008

Alfred Tomason, 2008

When vampire-child Eli (Lina Leandersson) says she's "been this age for a long time," there's no smile on her face. Just the grim emotion of a life forever on the cusp of adulthood. Sometimes I wonder if vampires age mentally, or if, despite the passing of centuries, a child like Eli still thinks like a twelve-year-old. Certainly she gives the appearance of youth, as when she befriends Oskar (Kare Hedebrant), a boy who has problems with bullies at school. But while Oskar is meek and twitchy, Eli is slow and deliberate, mature in her behavior, and the story suggests that she may be more than befriending Oskar. Near Dark and Interview With the Vampire similarly toyed with people destined to be children forever, but neither fully devoted themselves to the methodology and sadness that such a circumstance would require. Let the Right One In focuses on that idea, takes it as far as possible, and produces one of the best vampire movies of all time.

04. The Mist

Frank Darabont, 2007

Although Stephen King's original novella was written decades before, Darabont's adaptation hums with the anxiety of post-9/11 America. Both timeless and intractable from its period, The Mist focuses on the ramifications of a community drowning in fear, searching desperately for someone to blame. Divisions spike between people of different races, classes, and ultimately creeds, as the mysterious vapor traps residents of a Maine town inside a grocery market. Like Dante's Homecoming, The Mist is baldly political, with its heroes as leftist paragons of rationality, its chief villain a religious nut who gains traction with the Biblical implications of the disaster. "Implications" being the creative and grotesque monsters slouching behind the shadow of the mist. Darabont directs the suspense scenes with flair, and the creative monster design contributes to the feeling of an entire world intruding on our own. And the ending is one of the boldest in genre history.

03. The Descent

Neil Marshall, 2005

With The Descent, Neil Marshall mixes the fear of claustrophobia and the fear of being consumed. It's remarkably easy to do so. Caverns look uncannily like the insides of some enormous beast. Facing those fears are the two dominant players: Sarah (Shauna MacDonald) and Juno (Natalie Mendoza). Their peaceful world of extreme sports shatters with an event stunning in its random cruelty. After coping for a year, the two girls hope to recuperate through cave diving. The spelunking alone provokes enough suspense for two movies, especially in one terrifying sequence when Sarah's stuck in a small shaft while the rocks above weaken and crack. Similarly, when the monsters arrive, Marshall directs with flurries of energy, keeping the viewers unsure of what they can see, which ties into a shocking moment when one cave-diver gets disoriented and makes a crucial mistake. Dog Soldiers was energetic fun, but this film plumbs greater depths.

02. Shaun of the Dead

Edgar Wright, 2004

This is not a parody. This is one of the most accurate pictures of zombiedom ever. Because slow zombies are not terrifying anymore. If you'll notice, the past ten years saw running zombies, singing zombies, armed zombies, Nazi zombies, talking zombies...basically, anything that would improve upon the simplicity of Romero's original vision back in 1968. Shaun, however, embraces Romero's vision, but has the good sense to place it in a fresh context. The zombies are still blameless, the people done in by their emotional baggage. But now the zombies face desensitized losers, and the heroes of the film take the opportunity to get rid of some old records by throwing them like ninja stars. So much of the film depends on the precision of storytelling - every detail is a Chekhov's Gun - and the rest comes from the capable cast of Brits. They make the same damn mistakes from every other limp zombie movie, but they earn so much affection that they actually resurrect the drama.

01. Pulse

Kiyoshi Kurosawa, 2001

Kiyoshi Kurosawa, 2001

In Pulse, nothing is conquerable, because the antagonist is death. Not the practical joker of Final Destination or the hooded persona of The Seventh Seal, but the actual decay of life. All horror films are about death, of course, but so few have acutely keyed into the specter of oblivion. I can think of only a few. Romero's Night of the Living Dead, Lewton's The Seventh Victim. Definitely Pulse. Kurosawa offers up a scenario that terrifies with its totality. All of these characters are doomed, and, as viewers watching and experiencing their emotions, we too are doomed. The premise of the film hinges on how the Internet has somehow cued into the same wavelengths that form the afterlife, which is now spilling over into our world, but Kurosawa has no interest in the logic of his story. He's fascinated by the emotions it inspires, the images it evokes, the colors and the shots and the dread. One of the defining images of horror from the past decade is a ghost slinking down a hallway with liquid slowness. Why hurry? It has all the time in the world. We don't.

No comments:

Post a Comment